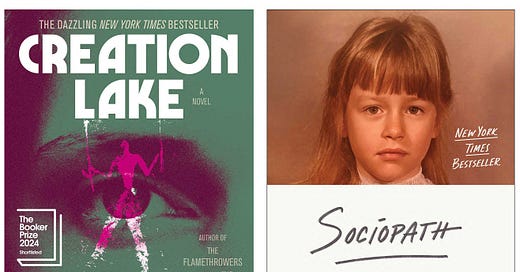

Little Peace: Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner

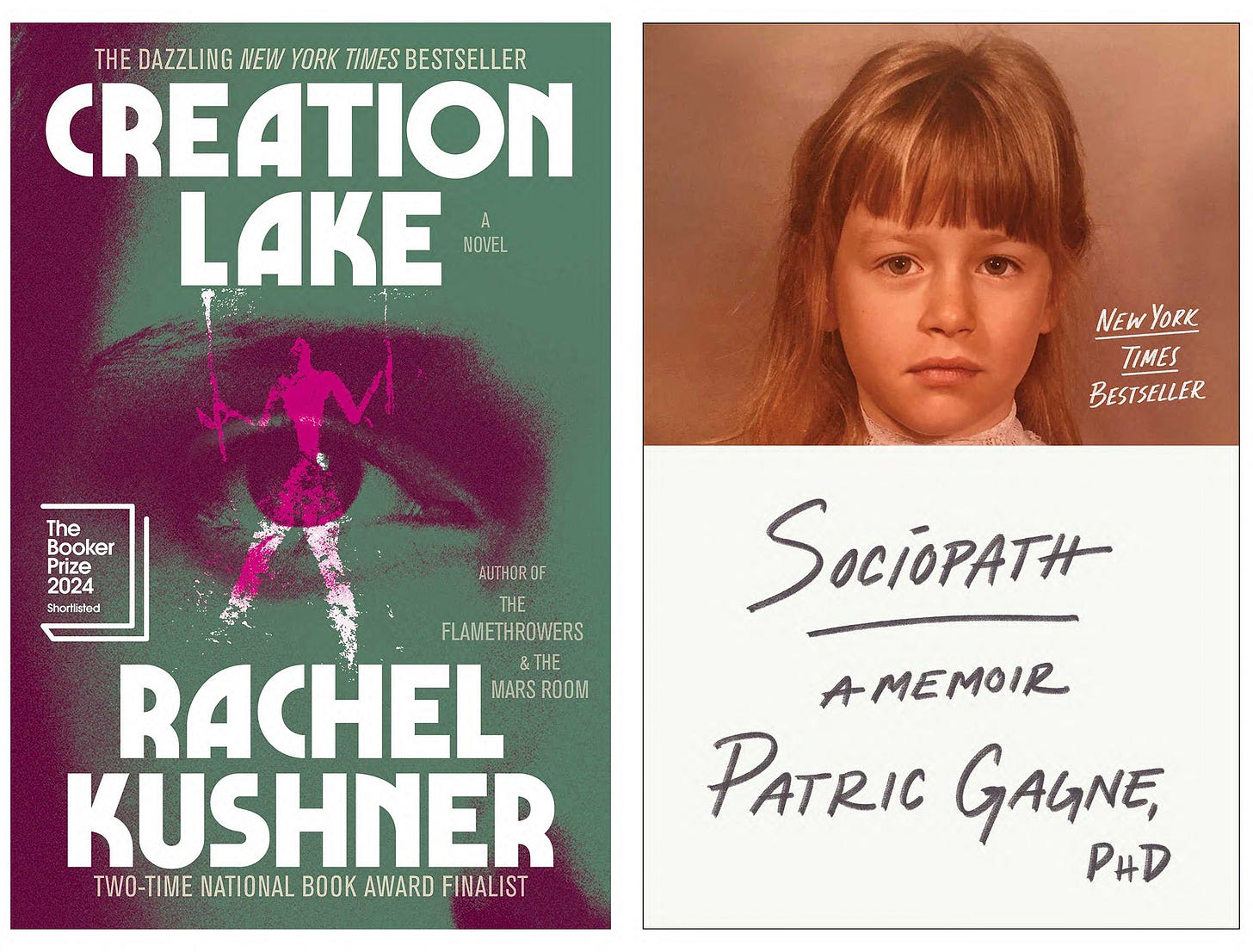

Plus Patric Gagneʼs Sociopath: A Memoir and touching grass in 2024.

In her remarkable Sociopath: A Memoir, Patric Gagne describes being on the sociopathic spectrum as a sort of blankness. Itʼs not that emotion is inaccessible, necessarily, but it’s been dialed down to a low hum, perceptible largely in the moments when sheʼs made to feel ashamed of its absence. Love is a deeply subjective experience, yet most of us can access a reasonable shared definition. Not so for Gagne.

“Certain emotions—like happiness and anger—came naturally, if somewhat sporadically,” she writes. “But social emotions—things like guilt, empathy, remorse, and even love—did not. Most of the time, I felt nothing.”

Gagne’s Sociopath helped me unlock Rachel Kushnerʼs Creation Lake. Kushnerʼs pseudonymous protagonist, Sadie Smith, is a cipher. She experiences the world through a scrim, all sensation and action held gingerly at armʼs length. As a mercenary honeypot-for-hire, this is an asset. Tasked with infiltrating a farming commune in the south of France at the behest of a shadowy, deep-pocketed patron, the gym-toned and surgically enhanced Sadie cozies up to the childhood best friend of the groupʼs de facto leader, while hacking into the shared email address the group uses to communicate with its elusive founder, the aging primitivist Bruno Lacombe. Bruno, it appears, has retreated to a cave somewhere in the regionʼs foothills and largely ignores the groupʼs pragmatic questions in favor of penning lengthy paeans to the moral superiority of Neanderthals, whom he affectionately calls Thals. “Perhaps Thal, he said, was a man graced with good qualities, and H. sapiens, in his plunder and advance toward the devastating dawn of agriculture, was a man with no such grace, a man without qualities, who substituted violence for the hole at the center of his heart.”

Sadie, too, has a hole at her center; she’s more of an unknown than any of the people she has been sent to surveil (and frame, should they lack any incriminating motives of their own). Her targets are almost painfully earnest in their eco-activism and belief in the self-organizing nature of the commune, never mind that the women have still mysteriously wound up caring for the children and preparing all the meals. And Brunoʼs myopic obsession with Thals is almost endearing in its transparency—a man yearning for a simpler time so literally that he wishes to yank human evolution back a few tens of thousands of years. “Of that moment when man first sparked fire—if such a moment could be isolated, and more and more these days he believed it could not be, in the sense that to believe in an original moment you had to believe in clock time, in calendar time, and he was dispensing with those concepts—he told Pascal and the group that although he himself was a crudivore, meaning he forwent the cooked, he did not reject fire completely. He maintained a hearth and used it. He said he built small fires. He said only a fool makes a large fire. He repeated this in a few different emails he sent them, like a mantra, a slogan, a cryptic cue.”

But what is it that Sadie wants? Nothing, it seems, other than to get the job done. To the extent that she has emotions, they are limited to revulsion (for her pretend fiancé, Lucien) and arousal (for a married member of the commune, with whom she has a brief and savage affair).

In Sociopath, Gagne describes a persistent, mounting sense of “pressure” that can only be relieved with a transgressive act: breaking into a home, stealing a car, or, once, stabbing a classmate. She attributes this sensation to the psychic discomfort of knowing that her response to the world around her is wrong but not knowing how to change it. She doesnʼt react to pain, drama, or trauma the way others expect her to, and it freaks them out.

Iʼm not usually in the business of armchair-diagnosing fictional characters, but itʼs telling that Sadie comes alive only when she is transgressing. She takes great pleasure in trashing Lucienʼs family cottage, blackmailing his auntʼs (admittedly skeevy) partner, and baiting her loverʼs wife. In contrast, she all but sleepwalks through her surveillance activities with the nonchalance of someone who’s seen it all before. She evaluates people and situations with the cold eye of the appraiser; they are noteworthy only to the extent that they are useful to her.

Yet Sadie is increasingly entranced by Brunoʼs pastoral fantasies, devoting hours (and whole pages) to his screeds. The parasocial bond she forms with him cracks open the emptiness at her core, motivating an about-face once her mission is carried out—the group successfully framed and a pompous politico summarily dispensed with, although it unfolds in a series of darkly comical mishaps I didn’t see coming. The denouement is surprisingly tidy for such a subtle and cynical book, with Sadie pursuing a purer, possibly transient, sort of contentment in a remote Spanish village: stargazing, solitude, swims in a sea “so salt-rich that I floated almost out of the water.”

Thereʼs no Creation Lake in Creation Lake. Nor is there a real Sadie Smith. Whoever Sadie Smith really is, she is as inaccessible to the reader as the real Patric Gagne is to anyone who is not a sociopath.

I canʼt help but be fascinated by characters like Sadie and people like Gagne—people who can shake off emotion as a duck does water. In contrast, Iʼve walked through large parts of my life as a raw nerve, every memory a wash of pure feeling. At times it feels like Iʼm still in love with everyone Iʼve ever been in love with; I regularly seize up in shame at the memory of some stupid thing I did twenty years ago. (Anyone else give a speech about David Bowie to their ninth-grade English glass wearing lilac eyeshadow under their eyes and speaking in a British accent? No?)

There have been times in my life when milder transgressions than Gagneʼs kept those feelings at bay—your standard adolescent and post-adolescent rebellion, which I wonʼt get into here because my mother reads this. These days, like Sadie, Iʼm keeping it together with more wholesome pursuits: climbing, hiking, aerial silks, making terrible pottery. Anything that reminds me that I am also a body and not just a mass of electrical pulses tapping out anxious messages in frenetic Morse code. Itʼs working pretty well. Iʼve touched more grass this year than I have in a long time. Iʼve scrambled up walls and pretzeled my limbs and been covered in clay and paint and chalk (not all at once). Iʼve met the coolest people and reconnected with dear friends and gone on adventures with my partner. The manic thrum at my center is quieter, at least for now.

I donʼt aspire to be a sociopath, but a little peace never hurt anybody.